| The Realms of Gold A New Novel by Terry Stanfill Available Now! |

|||||

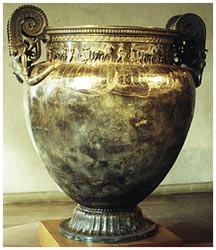

My own discovery of the Krater of Vix. It was in 1994 that I came upon le Cratère de Vix, an object I would soon come to learn is one of the best kept secrets in France, even to this day. My husband and I were on a road trip with our friend, Robin Tait from Paris who was making an annual purchase of Chablis and Pinot Noir from his favorite vineyards of la Côte d'Or, Burgundy. That Sunday we were on our way to the 12th century Abbey of Vézelay, one of the most spiritual, most celebrated sites in France. While Dennis and Robin chatted about Grand Crus and where to find the best vin de pays, I sat curled up in the back seat, looking over guidebooks in preparation of our stop at Vézelay Abbey, now called the Basilica of St. Mary Magdalene.  Author Terry Stanfill next to The Vix Krater As I thumbed through the Michelin Green Guide to la Côte d'Or, I stopped to stare at the photo of a bronze object discovered in 1953 buried near the banks of the river Seine, at the foot Mont Lassois, a mesa-like hill once a citadel of early Hallstatt Celts, traders with the Etruscans and Greeks of Magna Grecia, the Greater Greece of southern Italy. I convinced Dennis and Robin that we should take a detour to have a look at this wondrous object. And when we beheld it we gasped, taken aback by its massive size and stance. We all agreed that the experience was well worth the detour. For me, it was a revelation and the inspiration for my novel, The Realms of Gold.

What made this gigantic vessel even more intriguing was the discovery of the remains of a woman of about thirty years old, laid to rest in her wagon, its wheels removed and propped against a wall. A black-figure Attic kylix of Amazons battling Greek hoplites and Amazons, found amidst the stone and rubble, dates the tomb precisely as mid-6th century B.C. Eerily beautiful, the handles of the Krater depict gaping-tongued, sharp -toothed, snake-tailed gorgons, those horrid sisters whose bulging-eyed gaze could turn men into stone, a familiar subject in archaic period Greek art, and a motif often found as the handles of vases. A frieze of helmeted hoplites and horses wraps around the rim of the vessel. Found lying nearby was the Krater's strainer and cover, centered with a statuette of a Kore, the Maiden, dressed in a Greek peplos.

Claude Rolley, the leading bronze expert, has written that this great Krater, the largest bronze vessel to come down to us from Antiquity, was most probably cast in Sybaris on the southern Adriatic. In 510 B.C, this city of rich, luxury-loving Sybarites was destroyed by its rival, Kroton. After the defeat, the Krotoniates diverted the course of the river Crathis to inundate the ruined city so that it could never be inhabited again. Excavations have been underway since 1968 when its exact site was finally located by archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania digging together with an Italian team. The newly developed magnetometer detected Sybaris, buried beneath 15-18 feet of earth and silt. How, I wondered, did this immense bronze Krater make its way from southern Italy to Latisco, a Celtic settlement near Châtillon-sur-Seine in Burgundy. In 500 B.C. the Hallstatt Celts inhabited the region of north Western France. On a hilltop by a river, surrounded by forests and fertile plains, Latisco became one of the most important sites for Celts who traded tin for Baltic amber, furs and salt in exchange for the coral and wine of the Greeks and Etruscans. My novel is a story told in the present, with vignettes from the past written by its protagonist, Bianca Evans Caldwell, nom de plume, Bianca Fiore. Bianca imagines how and why and with whom the great Krater made its long and difficult journey from the golden city of Sybaris to the golden hillsides of la Cote d'Or. |